Hartland Community Arts and the Hartland Public Library present

The Virtual Hartland Poetry Fest 2021

Thursday, April 29, 2021 7:00-8:30 p.m.

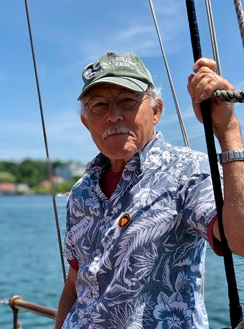

Robert S. Foote

Robert S. Foote is a retired physician and has lived in Hartland for many years. He is the author of a number of scientific research papers and essays and has been writing poetry since high school. His poems have been published in Dartmouth Medicine, Annals of Internal Medicine, UCLA Anthology of Poetry by Physicians, The San Diego Reader,various literary journals, and on “The Writer’s Almanac” on National Public Radio.

Robert S. Foote

At the Norcross Quarry,

Mount Ascutney

I think now that the simplest

questions are not only the hardest

to answer but the most important

to ask.

—Northrop Frye

It was a simple out and back, a hike

Just up the mountainside a mile or so,

To listen to the quarried stones, as though

At any moment I might hear the strike

Of sledge on hammer-drill, the warning shout,

The creak of cantilevered beam, the chuff

Of sweating horses struggling on the rough

And rutted mountain road. A thread of doubt

About the ends of things.

It was, they said,

The telltale trace of iron, the ochre stain

That grew and grew more dark with every rain,

All down the distant cities’ grand façades,

That doomed this place a hundred years ago.

A silent ruin now—a spike, a rail,

A horseshoe spills its luck into the swale;

Among abandoned stones great hemlocks grow.

In the painted valley past the bluff

The angled light grows warmer as it dies—

Although I know the warmth is in the eyes—

I do not know if I have seen enough.

So what is a place? How does it give

The power to be? Is it the power to reveal

That only the particular is real,

That only the imagined self can live?

It was nearly dusk; though still the great

Mountain loomed above, I had stayed late,

So I went down by the way I came,

Toward the place where I had started,

Wondering if it would be the same

Place that it had been when I departed.

___________________________________

An Interruption

A boy had stopped his car

To save a turtle in the road;

I was not far

Behind, and slowed,

And stopped to watch as he began

To shoo it off into the undergrowth—

This wild reminder of an ancient past,

Lumbering to some Late Triassic bog,

Till it was just a rustle in the grass,

Till it was gone.

I hope I told him with a look

As I passed by,

How I was glad he’d stopped me there,

And what I felt for both

Of them, something I took

To be a kind of love,

And of a troubled thought

I had, for man,

Of how we ought

To let life go on where

And when it can.

_____________________________

Assignment

You are to write an essay.

It counts for 100% of your final grade.

Be precise but complete. There are no guidelines as to subject,

style, content, length, or criteria for assigning grades. The

required language, English or other, will be announced after

your essays are collected.

Copying the work of others may be counted for or against you.

There are limited supplies of pens and paper, not enough for all

participants. Supplies will be distributed randomly. Those

without supplies are still required to complete the essay.

Some of the pens will not have enough ink to complete your

essay; incomplete essays will lower your final grade.

There are assistants assigned to make distracting noises or to

switch off the lights by which you are writing. You will receive

no credit if this happens to you.

There is a time limit; a buzzer will sound, and you must stop

writing immediately. Anything written after the buzzer will be

deleted.

The buzzer will sound at different times for different

persons, sometimes with advance notice and sometimes without.

All grades are final.

Please begin.

Samantha Kolber

The recipient of a Ruth Stone Poetry Prize and a Vermont Poetry Society prize, Samantha Kolber has had poems published in Rattle, Oddball Magazine, Mom Egg Review, Hunger Mountain, and other journals and anthologies. She received her MFA from Goddard College and completed post-grad work at Pine Manor College’s Solstice MFA Program. She lives in Montpelier, Vermont, where she coordinates events and marketing for Bear Pond Books and is the poetry series editor for Rootstock Publishing. Her chapbook “Birth of a Daughter” was published with Kelsay Books in 2020. Read and listen to her poems at her website, samanthakolber.com.

In Springtime: An Abecedarian

At winter’s

beginning, we think of snow

cover. We

don’t think of melting, when

Earth will be uncovered, or released

from prison. In springtime, the sky will be

grey, the grass, brown,

heavy with littered crumbs, gum wrappers, cigarette butts, Styrofoam cups.

In springtime

jays might swoop to

kill the newly thawed worm. In springtime, dog shit

like mud will

match bare trees, bare as

November.

Only

Persephone will

quit her moaning. She’ll

rise up to greet the

spring,

turn mud and dirt and long shat shit into the long-awaited

uncovering,

veering hidden songs into a

wail

’xactly when

yonder cow will moan the loamy

zap of babe’s first cry.

___________________________________

Birth of a Daughter

I birth myself anew

as I birth you, daughter.

I am me plus and minus the cells expunged

to create you, daughter.

You arrive, doll-sized, bright-eyed, a sponge

soaking up my milk—

more cells I shed to make you, feed you,

daughter. Am I the mushroom—

the fleshy, spore-bearing fruiting body

of a fungus, or are you? Or do we

form one as a verb? Do we mushroom

into this life, together, daughter?

I write this as you are away; we call it school,

though it is June and you are three.

I work, I write, I sit outside

in the sun, and I can’t lie: it’s delicious,

this time away from you;

it’s precious, as are you.

It has only taken me 42 years to realize

I am precious, too.

* From Birth of a Daughter by Samantha Kolber (Kelsay Books, 2020), printed with permission of the author (samanthakolber.com).

________________________________

Waiting for the Rise

I’m sorry Earth is closed today, reads the marquee

at the local theater we drive past on our way to Mirror Lake

to teach our daughter how to fish. We arrive to find

an eggplant-shaped pond, and the girl—almost four &

not yet hardened by life’s carapace—takes each worm

out of the bin, sets them free in mud.

Earth is not closed here: dirt road, golden light, steep rock,

evergreens, and the water I squint at: the glint of ripples

and the lethargy of fishing poles cast, red and white baubles waiting

for the rise. Husband and daughter bookended at the tiny shore,

lined up like paperbacks on a bookshelf—only their spines visible,

soft, loved, waiting. My son and I head out for a walk.

He, eighteen, all tall muscle, none of the spit & vinegar of teens,

nor the rebellion I dabbled in as a troubled one. What did I have

to be troubled about back then? No quarantine,

no hashtag bullies, worst of them the POTUS pushing

fat-thumbed octothorpe lies and AstroTurf rallies.

We came out here to breathe; to forget the news; to be

somewhere distant. Teach our daughter how to fish

as our son climbs boulders. Watch fish rise below as a great heron

flies above. Look up at this clear blue sky, let our thoughts

and fears loose, like a peristeronic message set free.

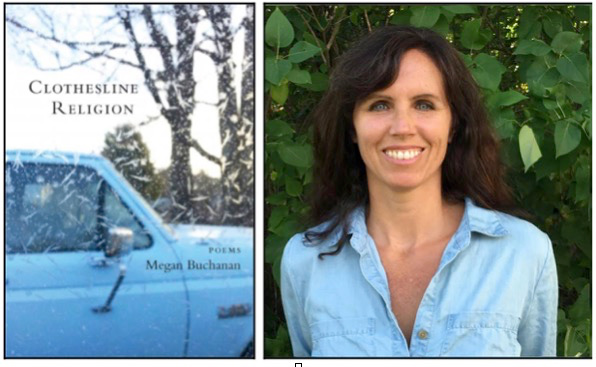

Megan Buchanan

Megan Buchanan is a teaching artist: a poet, performer, collaborative dancemaker, and high school English teacher. Her poetry collection Clothesline Religion (Green Writers Press, 2017) was nominated for the 2018 Vermont Book Award. Her poems have appeared in The Sun Magazine, make/shift, A Woman’s Thing, featured on public display at Art at the Kent in 2020, as well as in many other journals and numerous anthologies including most recently Dream Closet: Meditations on Childhood Space (Secretary Press), Roads Taken: Contemporary Vermont Poetry, and also Healing the Divide: Poems of Kindness and Connection (GWP). She’s currently part of the collaborative project Writing the Land.Her work has been supported by the Arizona Commission on the Arts, the Vermont Arts Council, Vermont Performance Lab, and the Vermont Studio Center. She lives in Putney. www.meganbuchanan.net

My Daughter’s Hair

I haven’t yet been able to find words –

a sentence for what happens when I brush

my daughter’s hair and divide into thirds

enough hair for a family of four

(one barber said, the rare one I trusted).

Honeycomb-colored braid, she’s out the door

for school (green coat, pink backpack), and rushing

right on time, little Virgo, to the bus.

One-woman-show with harmonies, alone –

amazed, bowed down (deep inhale) O the joy

contained in waves on waves: a shimmering song

my daughter’s hair sings as she floats

each afternoon high up into a tree.

Against the clouds she climbs, far beyond me.

_____________________________________

Naked Lady (Amaryllis Belladonna)

Leafless, her pink star head atop a foot-tall stalk,

leaning where you least expect bulbs to bloom:

alleyways, gravel edges of gas stations, laundromats.

I’ve seen her bloom beside steel poles bearing street signs,

on a hill at the edge of town, and out back of my house.

Naked Lady.

Her scent is the thing, unbelievable.

She’s more than tough and pretty –

she catches the light.

And when your nose pokes inside her bell,

that feathery sugarflower breath

makes you want to blow a bubble.

Imagine the ice cream flavor: NAKED LADY.

Longlegged, pink hat-headed Naked Lady,

my kind of girl, backroads and railroad yards.

Dishwater, rainspout survivor. Beautiful,

leaning against old houses in her bare feet,

out beneath my California clotheslines,

bordered by midnight raccoon/possum/skunkpath,

tomato plant forest.

She’s there at the edge of town, most obscenely

and courageously leaning naked

at all hours in her perfect pink hat.

You can’t miss her.

*from a Midsummer Night’s Dream

____________________________________

Singing at Matt Malloy’s

Westport, County Mayo

And afterwards when

sober, red-faced uncles

grabbed me for a dance,

that freedom

I’ve always been chasing

was mine and I hung on (eyes

closed against the tourists)

whirling round the center,

grinning as we flew

and stomped just so.

The music roared in my head

like the fierce hum of sea

inside a shell – salty

and unending

and for long moments

I was entirely possessed

by that ordinary magic.

Taylor Katz

Taylor Mardis Katz is a poet, farmer, and shopkeeper living in Chelsea, VT. With her husband, she runs Free Verse Farm & Apothecary and the Free Verse Farm Shop, and parents a small and fantastic human. Taylor’s poems have appeared in a variety of traditional and non-traditional publications and spaces and she is continually inspired by poets thinking outside the gridlines of traditional publishing models. She also works as a poet for hire, writing poems for strangers who find her on the internet. Equipped with her MFA from San Diego State University and an excellent hat selection, Taylor firmly believes that there is no place that poetry can’t go.

Is It Just Going To Be Me In This Body-House?

I’m heavy with hair,

my gums slouch

beneath their little white bones,

and just yesterday

my knees requested time off

from the rest of my skeleton.

I try mingling

with balloons—I mimic

the tinny whines

of wind chimes—

I place my limbs

in the shape of maples

whose branches never tangle.

I slip on someone else’s

sensible leather shoes,

weave my arms

into someone else’s

crocheted sweater,

let the breeze squeeze itself in.

The heaviness in me invents

new zip codes

in which to thrust

its luggage.

I try looser pants

and unleavened bread;

I abstain from big thoughts

and dairy products

yet find myself

pouring eggnog into my coffee

while considering

the role of technology

in our planet’s demise

and how I desire so much

the accidental crash

on the way out

of a dimly lit bar bathroom:

two strangers laughing

wiping gin off our chins

the room thick

with bodies and lit

from above and us

from within

while outside my windows the first snow of the season

quilts summer’s chairs.

________________________________________

To make soup

To make soup

you must pinch

off sections

of pork

add salt

and the herbs

you grew last summer

from the glass jar

that used to hold jam

and before that pesto

and before that

homemade butter

made by a friend

who milked

a borrowed cow

named Sorrel

twice a day all summer with four kids

back at the house

the baby watched

by her 3-year-old brother until their mother came back

with the goods—

And the sting

of onions lingers

in your eyes

and there are carrots

diced

dug out of wood shavings

from a crate

in the basement

plus one red pint

of stewed tomatoes

harvested the day before

the frost: end

of the workday

on your knees

laughing with the crew

because the buckets

you brought

are farcically small—

And two quarts

of chicken stock

boiled for a day

from a carcass

of a bird

raised by your friend

who for one full summer

wrangled lymphoma

instead of haying equipment

and these days

makes ice cream

so good

that people can’t help

saying “orgasmic”

about the dark chocolate pints—

And there is holiday jazz

on the speaker

and soup steam

blurs the windows

and you know

for certain

for this one

minute only

that you will survive

this winter

not because

you are stronger

or smarter

or have unearthed

some great secret—

but because

with each stir

you can find

all your friends

in the soup pot

_____________________________________

Hope in the Trees

The stillness of August

arrived today

the birds heading out

the bugs all cocooned

the wetland sucked dry

by the feet

of the backyard willows

which catch my eye

from the second-floor bedroom

each early spring

with what I am annually convinced

must be perfectly placed

orbs of snow attached

with precision

to the sky-swaying branches

for all I know of life

at that time

is snow on snow

on trees,

but what is instead,

miraculously,

each time miraculously,

the first sign of spring—

the downy fluffs

of pussy willows

clinging to the branches

having just exposed

their fur

to the world

for the first time,

again.

Peter Money

Peter Money’s work has appeared in The Sun, American Poetry Review, North Dakota Quarterly, Provincetown Arts, Hawai’i Review, on The Writer’s Almanac, RTE, and elsewhere. His books include co-translated poems with Sinan Antoon, Nostalgia, My Enemy by Saadi Youssef (Graywolf Press), the novel Oh When the Saints (Liberties Press, Ireland), a novella Che (BlazeVox), and several books of poems. His spoken word CD, Blue Square, with composer Mike Salvatoriello, is available on Apple Music. Last year, his pandemic poems were published as Harbinger, or HAR DEE HAR HAR. The former director of Harbor Mountain Press, Peter previously edited the literary journals Writers’ Bloc (Oberlin), Lame Duck (Brooklyn/San Francisco), and Across Borders (Lebanon). With Partridge Boswell and Nat Williams, he is one third of the poetry band Los Lorcas.

The Proof

James takes me around the bend

to where they are,

a river pool,

a shoal out in the middle sun,

thick tree curved for a seat

four feet above water

to where we can see bottom,

freckled like our skins.

“But I suppose,” he figures,

“it is a lot of things”

—meaning what he is doing,

what I am;

—our golems, our mountains.

You could say.

And this is fine for now.

For all we are here to do

is to say.

________________________

The Action

The water

lets the fish down.

an act of distraction

—or a call to

my name,

see:

a pearl in a time

of war.

Didi Jackson is the author of MOON JAR (Red Hen Press, 2020). Her poems have appeared in The New Yorker, New England Review, and Kenyon Review. She lives in Nashville, TN and teaches creative writing at Vanderbilt University. She recently rescued a puppy who truly puts the word terror in terrier.

SIGNS FOR THE LIVING

Sometimes, after the last snow in May,

after the red-winged blackbird clutches the spine

of the cattail, after he leans forward, droops

his wings and flashes his epaulets, I imagine

shouldering the yellow center lines of the road.

Near the recently thawed pond, within a long

channel of construction, a man holding a sign.

One side says slow, the other stop.

Joy and sorrow always run like parallel lines.

Inside the house, when I leave the lights on,

small white moths come like a collection of worship,

pulsing their wings up and up the window,

as if in a frenzied trancelike dance,

some dervishes, others the penitent on shaky knees.

The first few years after my husband’s suicide

I wanted to be the penitent.

I thought I deserved all the pain I could feel.

The drill of road work in late summer

was a welcome grinding music.

Now the yellow center lines are flung like braids behind me.

__________________________

MOON JAR

My wedding ring is missing

one small diamond, and

I like it that way: a reminder

of the imperfect in

all of us, like that keyhole

size of grief that remains crystalline.

In Korea, ceramicists for centuries

have made moon jars: testimony

to the virtue of modesty: asymmetrical

warping on the wheel, slumping

in the pine-heated kiln,

impurities when fired — black

dots and pocks on its surface

like freckles on skin.

I have been kept awake

so many nights by the moon:

its pull on the pines and night birds

and who, like a monk, keeps a sharp order of time.

Never a perfect sphere,

the milky moon jar joins two

clay hemispheres into one.

When the light of the moon

finds me, I am the color

of everything in the winter night.