Hartland Community Arts and the Hartland Public Library present

The Virtual Hartland Poetry Fest 2022

Wednesday, April 13, 2022 7:00 p.m.

To attend the event on Zoom, you’ll have to pre-register.

Robert S. Foote

Robert S. Foote is a retired physician and has lived in Hartland for many years. He is the author of a number of scientific research papers and essays and has been writing poetry since high school. His poems have been published in Dartmouth Medicine, Annals of Internal Medicine, UCLA Anthology of Poetry by Physicians, The San Diego Reader, Northern Woodlands, various literary journals, and on “The Writer’s Almanac” on National Public Radio.

Jim Schley is author of two volumes of poems, the chapbook One Another and the full-length collection As When, In Season. He has worked as a book editor for many years, including as editor-in-chief of Chelsea Green and managing editor of Tupelo Press, and now primarily with New Directions, Wesleyan and Brandeis University Presses, and Milkweed Editions. He has also been executive director of The Frost Place museum and poetry center. He toured internationally with Bread and Puppet and the Swiss troupe Les Montreurs d’Images, and in recent years has performed with Flock Dance Troupe, Parish Players, and BarnArts. He is a contributing writer for Seven Days, a book-discussion leader for Vermont Humanities, and lives on a land cooperative in Strafford, Vermont.

Laura Foley is the author of eight poetry collections. Everything We Need: Poems from El Camino was released, in winter 2022. Why I Never Finished My Dissertation received a starred Kirkus Review, was among their top poetry books of 2019, and won an Eric Hoffer Award. Her collection It’s This is forthcoming from Salmon Press. Her poems have won numerous awards, and national recognition—read frequently by Garrison Keillor on The Writers Almanac; appearing in Ted Kooser’s American Life in Poetry. Laura lives with her wife, Clara Gimenez, among the hills of Vermont.

Madre

As the train rumbles side to side,

as we leave the town of Clara’s birth,

we move into the hot, dry plain,

green after recent, sweet spring rains—

remembering how we sat

in her mother’s flat, abode of fifty years,

as thunder sang its omen tones,

as clouds—dark grey against still-blue sky—

let go their load on us, on the city,

on all of Spain, a heavy rain—

and how today the sky’s all sun,

swept clean after last night’s weeping.

This morning we crossed

the not-yet busy street, as her mother

leaned over the balcony,

her small frame bent with age,

her spine un perro rabioso que muerde—

a rabid dog she can’t bite back—

we and she called and waved,

as we turned the sunny corner,

our backpacks the last she sees of us,

as she turns away,

closing the casement window,

to sit alone and think of us.

Belief

Walking the endless Meseta, we turn to see

yellow broom flowers, orange poppies going by—

the only way to know these pilgrims’ progress.

Each night, an ancient town new to us,

steps closer to our journey’s end—

we feel no mystic pull toward Santiago,

but we believe in the awe of those who do,

as Gregorian chants pipe through a darkened church,

and a friend we meet weeps freely at a café table.

We leave Castrojeriz in the graying dark,

before dawn, before cafés open, our shoes

tapping a slow rhythm on quiet streets,

and though at this moment they’re empty of all but us,

we know the road, the path we’ve chosen,

takes us somewhere many have gone before.

We feel them all in the hard-packed trail,

in our aching feet,

in our will to keep going, a mysticism we can believe.

To Santiago

We began climbing in the year’s darkest days,

diagnosis in late November, turning trips

to the cancer center’s mountain into adventure.

Tying a scallop shell to her hospital backpack,

we metaphored illness as a pilgrimage to Santiago,

eight chemo treatments, followed by surgery.

We trekked December’s steep bitter peaks,

January’s icy valleys. How many miles, we’d say,

about halfway, sometime in snowy February.

We slogged on through a wet March,

a windy April that didn’t seem like spring.

Though our feet didn’t develop blisters,

her heart raced at an alarming rate,

she lost her hair, and her taste buds changed.

A bit metallic, she’d say, with grit.

As we approached surgery, in early May,

we searched the horizon for the cathedral,

knew the steeple would soon come into view.

Soon we’d descend the final hill to Santiago.

Soon the maroon-robed priests

would swing the Botafumeiro over our heads,

fill the vast space with cleansing fragrance

of myrrh and frankincense.

Soon we’d stroll along the beach

at the end of the world,

the beach that ends one world

and begins another, cancer

would become a wintry memory,

and our legs would rest, our stash

of metaphors ready, for the next quest.

Michael Metivier is an editor, musician, and writer. His work has appeared in publications including Poetry, North American Review, Crazyhorse, and Northern Woodlands and is forthcoming in Bennington Review and Kenyon Review. He lives with his family in Windsor, where he serves as the tree warden for the town. He is also on the governing board of the First Universalist Society of Hartland and works as an assistant editor at Merriam-Webster. His website is: michaelmetivier.com

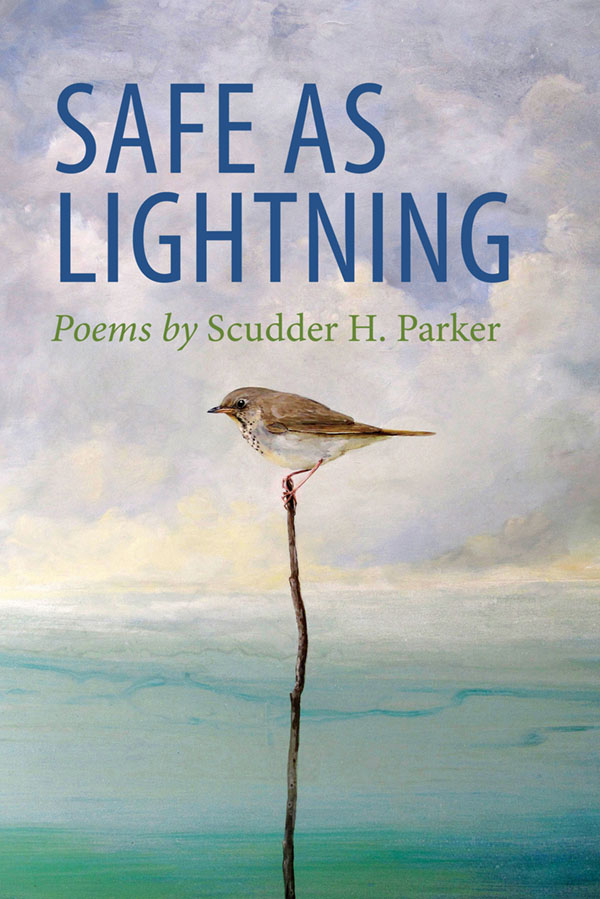

Scudder Parker grew up on a family farm in North Danville, VT. He is settling into his ongoing work as a poet and essay writer after careers as a Protestant minister, politician and energy efficiency consultant. His first volume of poetry “Safe as Lightning” was released in June, 2020, by Rootstock Publishing, and was awarded the Best Poetry Book of 2020 by the Independent Publishers of New England (IPNE). It was also featured in Kirkus Reviews “Best Books of 2020” issue.

Scudder’s poetry has also appeared in numerous literary journals including Sun Magazine, Crosswinds, The Lascaux Review, Northern Woodlands, Sky Island Journal, Vermont Life, Northern Woodlands, and Twyckenham, He is a passionate gardener and proud grandfather of four. He and his wife, Susan, live in Middlesex, VT. www.scudderparker.net

The Poem of the World

reveals itself

like a doe’s hoof tapping ice

till she can drink.

Startles like the rust of purple on this fall’s

forsythia leaves, though it may have used that small voice

every year, unheard.

Blinks like red and blue potatoes,

dug this morning, drying in the sun, testing

their startled untrained eyes.

It’s the unexpected tickle, the fit of shared

laughter in our urgency of touching that becomes

another way of making love. It’s an ocean

beach of pebbles that suddenly

starts singing, each stone its own tink;

together, a glorious indifferent song.

And it’s the voice of each bird I have only heard

as morning chorus landing with its own song

and bright perfect body in my brain.

It is even—now I begin to see them—the subtraction

of birds, taking summer with them, too busy

to announce their leaving.

The poem of the world wants me to wake

in my own body; it is astonished I might let

these supple bones grow brittle.

It is the sudden thing I trust.

Davy Road

A man in clothes the shape of sleep

pushes his battered bicycle,

wire baskets front and back,

halfway up the drive and stops.

He watches me raking gravel.

“You live here now?” I pause,

lean on my rake. “I’m trying.”

We gossip like old neighbors.

His family logged pine and maple.

A few cows and chickens. Some summers

a bear got all the corn. I tell him

a bear got ours last summer.

The house and barn were “down there,

where you have your woodpile now.

The house was small and cold as hell.

The barn was built better.”

We go down, explore lilac,

sprawling roses, honeysuckle,

clumps of double daffodils,

stacked granite slabs that held the barn.

No sign of the house foundation.

Five generations in this place,

and I, three years.

Twice since then I’ve seen him,

picking up empties. Once,

just his bike, leaning against a tree.

Gratitude

The peonies and gladioli are more

seductive every fall. I choose slips

of peony root with three buds full

of color that may prosper years from now.

I dig shaggy gladiola corms,

plumped on slender stalks, next year’s

replacements for the tough exhausted husks

left from the thrust of color-trumpets to the sky:

purple (steeped in black), regal crimson,

slim white Abyssinian, lavender

that cried out to sunset orange;

bulblets cling, intent on futures of their own:

Beauty’s nonchalant kindness

accepts the slow learning of my eyes.

A few days of October sun—they are

like gratitude, always a surprise.

I plant the slips; come in and sort the corms;

possessed by past and future blooms.

I remember how I dreaded

grownups who creaked like closing doors.

Even now I fear joy might never

be allowed back through my window,

but gratitude is a different eye that opens—

unnerving in its great permissions.

In sun, on this cold porch, I’m grateful.

Some shy part of me is always

sitting here, no wisdom, no plan; full

of psalms, no notion who I’m singing to.

Rebecca Starks is the author of the poetry collections Fetch, Muse (Able Muse Press, 2021) and Time Is Always Now, a finalist for the 2019 Able Muse Book Award; her poem “Open Carry” received Rattle’s Neil Postman Award for Metaphor. Her poems and short fiction have appeared in Epiphany, Crab Orchard Review, Tahoma Literary Review, Rattle, Slice, and elsewhere.

A co-founder of Mud Season Review and on the board of Sundog Poetry Center, she lives in Richmond and works as a writing consultant and workshop leader.

According to poet Betsy Sholl, Carol Westberg’s third collection, Ice Lands, is “a luminous and stunning book, blending grief with wisdom and awe.” Westberg’s Terra Infirma was a finalist for the 2014 Tampa Review Prize, Slipstream was a finalist for the 2011 New Hampshire Literary Award for Outstanding Book of Poetry, and “Tyranny of Dreams” was chosen for the NH poet laureate’s Poet Showcase. Her work has appeared in journals such as Prairie Schooner, Hunger Mountain, Valparaiso Poetry Review, and CALYX. She’s read at the Canaan Meetinghouse Reading Series and at Bookstock, among other venues. Carol earned a BA from Duke, an MA from Stanford, and an MFA in Poetry at Vermont College. She’s lives in Hanover, NH with her husband.